Persistent pain affects over 100 million Americans and contributes to over $600 billion dollars in indirect and direct healthcare costs in the US.1 In primary care offices, back, neck, headaches, and joint pain account for a majority of pain complaints. Globally, musculoskeletal pain the leading cause of disability.2,3 People seek pain management across a multitude of specialties and acuity settings, from emergency departments, surgical wards, podiatry clinics, and birth centers to dental offices, and long-term care facilities.4,5

Pain can also lead to a loss of productivity, and lowered quality of life.6 It can exacerbate or lead to other conditions, such as anxiety and depression, and can affect the well-being of family members and caregivers.7 It can also lead to a long-term dependence on analgesics, such as opioids. Untreated or inadequately treated pain can increase morbidity, prolong an injury or disease, and increase the cost of care.8,9

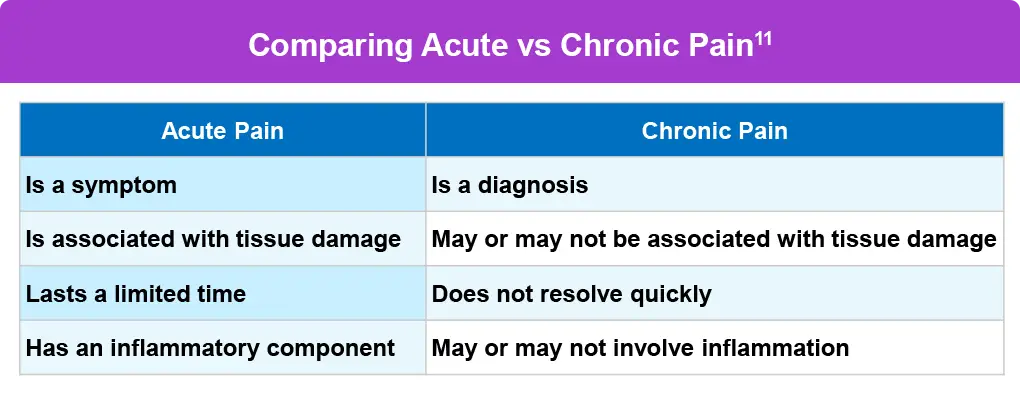

What is pain, exactly? In 2020, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defined pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage”.10 IASP adds a significant note that pain is always a subjective experience, and can vary through biological, psychological, and social influences.10 Pain can be acute, which can last a few seconds or up to days and weeks, subacute, lasting 6 weeks to 3 months, or chronic, which is any pain that lasts longer than 3 months.10,11 While subacute pain is a subset of acute pain representing ongoing healing, chronic pain itself can be a disease, called chronic primary pain, or indicative of an underlying disease or injury, where it’s called chronic secondary pain.3